10 body parts that are useless in humans (or maybe not)

There's some debate around which human body parts are useless and which aren't.

Does the human body contain any truly useless parts? Arguably, yes — but they might not be the ones you assume.

Some body parts, like the male nipple, arguably serve no useful function. But others, like the appendix, remain a matter of debate, as recent research suggests that they may serve a purpose scientists don't yet fully understand.

Scientists have a track record of rating organs' importance before learning their true functions. But the more we learn, the more we realize many of those "useless" parts are actually essential.

For example, in the 1890s, anatomist Robert Wiedersheim published a list of 86 human "vestiges," or body parts that had "lost their original physiological significance" to humans. The list, published in his book "The Structure of Man: An Index to His Past History (opens in new tab)," included essential anatomy, such as key valves in veins that help direct blood flow; the thymus gland, which makes disease-fighting white blood cells; and the hormone-producing pituitary and pineal glands.

Scientists continue to discover new things about the human body to this day. With that in mind, here are 10 of the human body's seemingly useless parts, some of which remain controversial.

Related: How many organs are in the human body?

1. Male nipples

In the womb, all human embryos initially develop all the same parts, and then about seven weeks in, the sexes begin to diverge, Michelle Moscova (opens in new tab), leader of the Healthcare Innovations research team at the University of New South Wales Sydney, wrote in The Conversation (opens in new tab). That's when a gene called SRY on the Y chromosome kicks in and jump-starts the development of male reproductive organs and the disappearance of female ones. Nipples start to form before SRY activates, so all humans end up with nipples, regardless of their sex. Although usually not capable of lactation, male nipples often still respond to sexual stimulation, so some may disagree with the idea that they're totally "useless."

2. Wisdom teeth

Humans' third molars, better known as wisdom teeth, can be used to chew food but are often considered unnecessary. In about 22% (opens in new tab) of people worldwide, at least one out of four wisdom teeth fails to grow in. When they do grow, the teeth are the most likely (opens in new tab) to become impacted, meaning they don't properly emerge through the gums. That's because humans' jaws are often too small to accommodate the teeth. Some scientists have chalked this up to humans evolving smaller jaws over time, but now, there's evidence to suggest that our childhood diets are more to blame. Consuming hard-to-chew foods, like raw vegetables and nuts, may stimulate jaw growth, while eating soft, processed foods somewhat stunts jaw growth, leaving little room for wisdom teeth, Discover reported (opens in new tab).

Related: Why do wisdom teeth come in so late?

3. The vomeronasal organ

In some humans — scientists aren't sure how many — remnants of a tube-shaped, pheromone-detecting organ can be found poking through the roof of the nasal cavity. This structure, called the vomeronasal organ or Jacobson's organ, is present and functional in many animals, including reptiles, amphibians and mammals. There's anatomical and genetic evidence to suggest that the organ is nonfunctional in the humans who carry it, but this matter is "still widely debated," per a 2018 review in the journal Cureus (opens in new tab).

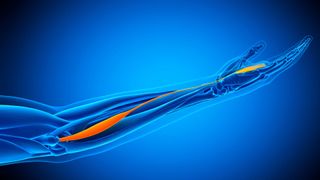

4. Palmaris longus muscle

The palmaris longus muscle extends from the bottom of the upper arm bone, or humerus, to thick connective tissue, or fascia, in the palm of the hand. Functionally, it's one of the muscles involved in flexing the hand at the wrist and in tensing the palm — but not all humans carry the muscle, and those without it can still execute these motions without issue. Some scientists theorize that the muscle is stronger and more functionally relevant in tree-climbing primates than in land-bound primates, like humans, according to a 2014 report in the journal Medical Hypotheses (opens in new tab).

5. Pyramidalis muscles

The two pyramidalis muscles originate at the joint between the two pubic bones — the pubic symphysis — and extend to each side of the linea alba, a line of connective tissue that runs down the center of the abdomen. These muscles vary in size, and a percentage of humans are missing one or both of the muscles and suffer no ill effects from their absence, according to a 2017 report in the Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research (opens in new tab). Estimates suggest that between 10% and 20% of people are missing at least one pyramidalis muscle, but these estimates vary depending on the population of people studied.

6. Darwin's point

Darwin's point, or Darwin's tubercle, is a bump that sometimes appears on the rim of the outer ear. Considered a harmless malformation of the ear, the structure is thought to be a remnant of a joint that once allowed the top of the ear to fold down over the ear canal, New Scientist reported (opens in new tab).

7. Auricular muscles

The auricle, or pinna, is the visible portion of the ear on the outside of the head; the muscles attached to the auricle are considered vestigial in humans, meaning they've lost all or most of their original function over evolutionary time. ("Vestigial" is widely thought to mean "completely nonfunctional," but this is a misconception.) While many animals can pivot their ears in response to sounds, humans have lost this ability and some can't even wiggle their ears, according to The New York Times (opens in new tab).

8. The "tailbone"

The human tailbone, or coccyx, is also considered vestigial, meaning it's lost its original function over evolutionary time. Once part of an actual tail, the human tailbone now consists of three to five rudimentary vertebrae fused together to form a single bone; it serves as an anchoring point for many muscles, ligaments and tendons, New Scientist reported. So while it's far from useless, it's no longer a tail.

9. The appendix? (Maybe not.)

Charles Darwin first proposed that the appendix, a pouch-like structure that extends off the large intestine, might be a vestigial organ that once helped our herbivorous ancestors digest hearty plants. The fact that some people are born without an appendix and many have the organ surgically removed without any obvious consequence seemed to support this idea. But more recently, research has revealed possible functions of the appendix in a wide range of mammals, including humans. The organ may be a reservoir for helpful gut bacteria, for example, and also a site where disease-fighting immune cells are born. So is it useless? Maybe not, but get it removed if you have appendicitis.

10. "Third eyelid"

Birds, reptiles and some mammals, including cats, have a third eyelid that blinks across the eye, from the lower inner corner to the upper outer corner. This windshield wiper-like structure, called the nictitating membrane, doesn't exist in humans, but humans do carry a remnant of the third eyelid in the inner corner of each eye, according to Scientific American (opens in new tab).

This remnant, called the plica semilunaris, looks like a small, fleshy bump. Although sometimes thought to be useless because it doesn't function as an eyelid, it actually supports the rotation (opens in new tab) of the eyeball and helps with tear drainage. That said, the tissue may be removed in patients (opens in new tab) who require surgery for narrowing or blockage of the tear duct.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.