Amateur freedivers find gold treasure dating to the fall of the Roman Empire

The 53 gold coins date to the fourth and fifth centuries.

Two amateur divers swimming along the Spanish coast have discovered a huge hoard of 1,500-year-old gold coins, one of the largest on record dating to the Roman Empire.

The divers, brothers-in-law Luis Lens Pardo and César Gimeno Alcalá, discovered the gold stash while vacationing with their families in Xàbia, a coastal Mediterranean town and tourist hotspot. The duo rented snorkeling equipment so they could go freediving with the goal of picking up trash to beautify the area, but they found something far richer when Lens Pardo noticed the glimmer of a coin at the bottom of Portitxol Bay on Aug. 23, El País reported.

When he went to investigate, he found that the coin "was in a small hole, like a bottleneck," Lens Pardo told El País in Spanish. After cleaning the coin, Lens Pardo saw that it had "an ancient image, like a Greek or Roman face." Intrigued, Lens Pardo and Gimeno Alcalá returned, freediving to the hole with a Swiss Army knife and using its corkscrew to unearth a total of eight coins.

Related: Photos: Roman-era silver jewelry and coins discovered in Scotland

Stunned by the find, Lens Pardo and Gimeno Alcalá reported it the next day to the authorities. "We took the eight coins we had found and put them in a glass jar with some sea water," Lens Pardo said. Soon, a team of archaeologists from the University of Alicante, the Soler Blasco Archaeological and Ethnological Museum and the Spanish Civil Guard Special Underwater Brigade, in collaboration with the Town Council of Xàbia, came together to excavate and examine the treasure.

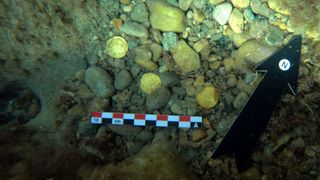

With the help of the archaeologists, they found that the hole held a hefty pile of at least 53 gold coins dating between A.D. 364 and 408, when the Western Roman Empire was in decline. Each coin weighs about 0.1 ounces (4.5 grams).

The coins were so well preserved, archaeologists could easily read their inscriptions and identify the Roman emperors depicted on them, including: Valentinian I (three coins), Valentinian II (seven coins), Theodosius I (15 coins), Arcadius (17 coins), Honorius (10 coins) and an unidentified coin, according a University of Alicante statement. The hoard also included three nails, likely made of copper, and the deteriorated lead remains of what may have been a sea chest that held the riches.

The hoard is one of the largest known collections of Roman gold coins in Europe, Jaime Molina Vidal, a professor of ancient history at the University of Alicante (UA), researcher at the University Institute of Archaeology and Historical Heritage at UA and team leader who helped recover the buried treasure, said in the statement. The coins are also a treasure trove of information, and may shed light on the final phase of the Western Roman Empire before it fell, Molina Vidal said. (In A.D. 395, the Roman Empire split in two pieces: the Western Roman Empire, with Rome as its capital, and the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire, with Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) as its capital, Live Science previously reported.)

Perhaps these coins were purposefully hidden during the violent power struggles that ensued during the Western Roman Empire's final stretch. During that time, the barbarians — non-Roman tribes such as the Germanic Suevi and Vandals and the Iranian Alans — came to Hispania, the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula, and took power from the Romans in about 409, according to the statement.

"Sets of gold coins are not common," Molina Vidal told El País, adding that Portitxol Bay is where ships leaving from Rome's Iberian provinces stopped before sailing to the Balearic Islands, which includes modern-day Mallorca and Ibiza, and then heading to Rome. Given that archaeologists haven't found evidence of a nearby sunken ship, it's possible that someone purposefully buried the treasure there, possibly to hide it from the barbarians, likely the Alans, he said.

"The find speaks to us of a context of fear, of a world that is ending — that of the Roman Empire," Molina Vidal said.

Related: Mayday! 17 mysterious shipwrecks you can see on Google Earth

So far, a study of the coins suggests that the gold hoard belonged to a wealthy landowner, because in the fourth and fifth centuries "the cities were in decline and power had shifted to the large Roman villas, to the countryside," Molina Vidal told El País.

"Trade has been stamped out and the sources of wealth become agriculture and livestock," he said. As the barbarians advanced, perhaps one of the landowners gathered up the gold coins — which did not circulate as regular money, but were collected by families to serve as signs of wealth — and had them buried in a chest in the bay. "And then he must have died because he did not return to retrieve them," Molina Vidal said.

After the coins are fully studied, they will go on display at the Blasco Archaeological and Ethnographic Museum in Xàbia. Meanwhile, the Valencian government has allocated $20,800 (17,800 Euros) for underwater archaeology excavations in the area, in case any more treasures are buried in the vicinity. Previously, Portitxol Bay has yielded other discoveries, including anchors, amphorae (ceramic vessels), ceramics and metal remains, and artifacts associated with ancient navigation.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Laura is the archaeology/history and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including archaeology and paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular

By Harry Baker

By Ben Turner

By Jamie Carter