Dark matter could be a cosmic relic from extra dimensions

Massive gravitons may have formed a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang, in abundances great enough to account for dark matter.

Dark matter, the elusive substance that accounts for the majority of the mass in the universe, may be made up of massive particles called gravitons that first popped into existence in the first moment after the Big Bang. And these hypothetical particles might be cosmic refugees from extra dimensions, a new theory suggests.

The researchers' calculations hint that these particles could have been created in just the right quantities to explain dark matter, which can only be "seen" through its gravitational pull on ordinary matter. "Massive gravitons are produced by collisions of ordinary particles in the early universe. This process was believed to be too rare for the massive gravitons to be dark matter candidates," study co-author Giacomo Cacciapaglia, a physicist at the University of Lyon in France, told Live Science.

But in a new study published in February in the journal Physical Review Letters (opens in new tab), Cacciapaglia, along with Korea University physicists Haiying Cai and Seung J. Lee, found that enough of these gravitons would have been made in the early universe to account for all of the dark matter we currently detect in the universe.

The gravitons, if they exist, would have a mass of less than 1 megaelectronvolt (MeV), so no more than twice the mass of an electron, the study found. This mass level is well below the scale at which the Higgs boson generates mass for ordinary matter — which is key for the model to produce enough of them to account for all the dark matter in the universe. (For comparison, the lightest known particle, the neutrino, weighs less than 2 electronvolts, while a proton weighs roughly 940 MeV, according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (opens in new tab).)

The team found these hypothetical gravitons while hunting for evidence of extra dimensions, which some physicists suspect exist alongside the observed three dimensions of space and the fourth dimension, time.

In the team's theory, when gravity propagates through extra dimensions, it materializes in our universe as massive gravitons.

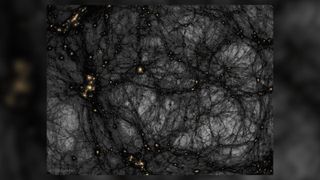

But these particles would interact only weakly with ordinary matter, and only via the force of gravity. This description is eerily similar to what we know about dark matter, which does not interact with light yet has a gravitational influence felt everywhere in the universe. This gravitational influence, for instance, is what prevents galaxies from flying apart.

"The main advantage of massive gravitons as dark matter particles is that they only interact gravitationally, hence they can escape attempts to detect their presence," Cacciapaglia said.

In contrast, other proposed dark matter candidates — such as weakly interacting massive particles, axions and neutrinos — might also be felt by their very subtle interactions with other forces and fields.

The fact that massive gravitons barely interact via gravity with the other particles and forces in the universe offers another advantage.

"Due to their very weak interactions, they decay so slowly that they remain stable over the lifetime of the universe," Cacciapaglia said, "For the same reason, they are slowly produced during the expansion of the universe and accumulate there until today."

In the past, physicists thought gravitons were unlikely dark matter candidates because the processes that create them are extremely rare. As a result, gravitons would be created at much lower rates than other particles.

But the team found that in the picosecond (trillionth of a second) after the Big Bang, more of these gravitons would have been created than past theories suggested. This enhancement was enough for massive gravitons to completely explain the amount of dark matter we detect in the universe, the study found.

"The enhancement did come as a shock," Cacciapaglia said. "We had to perform many checks to make sure that the result was correct, as it results in a paradigm shift in the way we consider massive gravitons as potential dark matter candidates."

Because massive gravitons form below the energy scale of the Higgs boson, they are freed from uncertainties related to higher energy scales, which current particle physics doesn't describe very well.

The team's theory connects physics studied at particle accelerators such as the Large Hadron Collider with the physics of gravity. This means that powerful particle accelerators like the Future Circular Collider at CERN, which should begin operating in 2035, could hunt for evidence of these potential dark matter particles.

"Probably the best shot we have is at future high-precision particle colliders," Cacciapaglia said. "This is something we are currently investigating."

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University

Most Popular

By Harry Baker

By Ben Turner

By Jamie Carter