Copper: Facts about the reddish metal that has been used by humans for 8,000 years

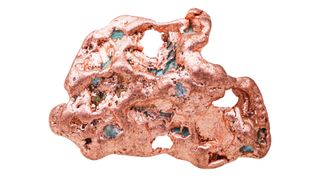

Copper is the only metal, aside from gold, whose coloring isn't naturally silver or gray.

Shiny, reddish copper was the first metal manipulated by humans, and it remains an important metal in industry today.

The oldest metal object found in the Middle East consists of copper; it was a tiny awl dating back as far as 5100 B.C. And the U.S. penny was originally made of pure copper (although, nowadays, it is 97.5% zinc with a thin copper skin).

Copper ranks as the third-most-consumed industrial metal in the world, after iron and aluminum, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (opens in new tab) (USGS). About three-quarters of that copper goes to make electrical wires, telecommunication cables and electronics.

Aside from gold, copper is the only metal on the periodic table whose coloring isn't naturally silver or gray.

Chemical description of copper

- Atomic number (number of protons in the nucleus): 29

- Atomic symbol (on the periodic table of elements): Cu

- Atomic weight (average mass of the atom): 63.55

- Density: 8.92 grams per cubic centimeter

- Phase at room temperature: solid

- Melting point: 1,984.32 degrees Fahrenheit (1,084.62 degrees Celsius)

- Boiling point: 5,301 F (2,927 C)

- Number of isotopes (atoms of the same element with a different number of neutrons): 35; 2 stable

- Most common isotopes: Cu-63 (69.15% natural abundance) and Cu-65 (30.85% natural abundance)

The history of copper

Most copper occurs in ores and must be smelted, or extracted from its ore, for purity before it can be used. But natural chemical reactions can sometimes release native copper, according to the chemistry database site, Chemicool (opens in new tab).

Humans have been making things from copper for at least 8,000 years and figured out how to smelt the metal by about 4500 B.C. The next technological leap was creating copper alloys by adding tin to copper, which created a harder metal than its individual parts: bronze. The technological development ushered in the Bronze Age, a period covering approximately 3300 to 1200 B.C, and is distinguished by the use of bronze tools and weapons, according to The History Channel (opens in new tab).

Copper artifacts are sprinkled throughout the historical record. The tiny awl, or pointed tool dating to 5100 B.C. was buried with a middle-age woman in an ancient village in Israel. The awl represents the oldest metal object ever found in the Middle East. The copper probably came from the Caucasus region, located in the mountainous region covering southeastern Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia more than 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) away, according to a 2014 article published in PLOS ONE (opens in new tab). In ancient Egypt, people used copper alloys to make jewelry, including toe rings. Researchers have also found massive copper mines from the 10th century B.C. in Israel. Copper may even have been the first pollutant that humans unleashed upon the environment, around 7,000 years ago.

About two-thirds of the copper on Earth is found in igneous (volcanic) rocks, and about one-quarter occurs in sedimentary rocks, according to the USGS. The metal is ductile and malleable, and conducts heat and electricity well — reasons why copper is widely used in electronics and wiring.

Copper turns green because of an oxidation reaction; that is, it loses electrons when it's exposed to water and air. This oxidation reaction is the reason the copper-plated Statue of Liberty is green rather than orange-red. According to the Copper Development Association (opens in new tab), a weathered layer of copper oxide only 0.005 inches (0.127 millimeters) thick coats Lady Liberty, and the covering weighs about 80 tons (73 metric tons). The change from copper-colored to green occurred gradually and was complete by 1920, 34 years after the statue was dedicated and unveiled, according to the New York Historical Society (opens in new tab).

Fast facts about copper

Here are some interesting facts about copper:

- According to Peter van der Krogt (opens in new tab), a Dutch historian, the word "copper" has several roots, many of which come from the Latin word cuprum that was derived from the phrase Cyprium aes, which means "a metal from Cyprus," as much of the copper used at the time was mined in Cyprus.

- If all of the copper wiring in an average car were laid out, it would stretch 0.9 miles (1.5 km), according to the USGS (opens in new tab).

- The electrical conductance (how readily a current can flow through the metal) of copper is second only to that of silver, according to the Jefferson Laboratory.

- Pennies were made of pure copper only from 1783 to 1837. From 1837 — 1857 pennies were made of bronze (95% copper, with the remaining 5% made up of tin and zinc). In 1857, the amount of copper in pennies dropped to 88% (the remaining 12% was nickel). In 1864, the recipe reverted to its previous recipe. In 1962, a penny's content changed to 95% copper and 5% zinc. From 1982 through today, pennies are 97.5% zinc and 2.5% copper.

- People need copper in their diets. The metal is an essential trace mineral that's crucial for forming red blood cells, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine (opens in new tab). Fortunately, copper can be found in a variety of foods, including grains, beans, potatoes and leafy greens.

- Too much copper (opens in new tab), however, is a bad thing. Ingesting high levels of the metal can cause abdominal pain, vomiting and jaundice (a yellowish tinge to the skin and white of the eyes that may indicate the liver is not functioning correctly) in the short term. Long-term exposure may lead to symptoms such as anemia, convulsions and diarrhea that is often bloody and may be blue.

- Occasionally, increased levels of copper are found in the water supply due to old copper pipes. For example, in August 2018, the public school system in Detroit (opens in new tab) turned off all drinking water in public schools as a precaution due to high levels of copper and iron found in the water, according to the Seattle Times (opens in new tab).

- Copper has anti-microbial properties and kills bacteria, viruses and yeasts (opens in new tab) on contact, according to a 2011 paper in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology. As a result, copper can even be woven into fabrics to make anti-microbial garments, like socks that fight foot fungus.

- Copper is also included in certain types of intrauterine devices (IUDs) used for birth control, according to the Mayo Clinic (opens in new tab). The copper wiring creates an inflammatory reaction that is toxic to both sperm and eggs, in order to prevent pregnancy. There is, with any medical procedure, a risk of side effects. (Copper toxicity doesn't appear to be one, according to a 2017 article published in Medical Science Monitor (opens in new tab)).

Current research

Copper's anti-microbial properties have made it a popular metal in the medical field. Multiple hospitals have experimented with covering frequently touched surfaces, such as bed rails and call buttons, with copper or copper alloys in an attempt to slow the spread of hospital-acquired infections. Copper kills microbes by interfering with the electrical charge of the organisms' cell membranes, said Cassandra Salgado, a professor of infectious diseases and a hospital epidemiologist at the Medical University of South Carolina.

In 2013, a team of researchers led by Salgado tested surfaces in intensive-care units (ICUs) in three hospitals, comparing rooms modified with copper surfaces attached to six common objects that are subjected to many hands to rooms not modified with copper. The scientists found that, in the traditional hospital rooms (those without copper surfaces), 12.3% of patients developed antibiotic-resistant infections such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). By comparison, in the copper-modified rooms, only 7.1% of patients contracted one of these potentially devastating infections.

"We know that if you put copper in a patient's room, you're going to decrease the microbial burden," Salgado told Live Science. "I think that's something that has been shown time and time again. Our study was the first to demonstrate that there could be a clinical benefit to this."

The researchers changed nothing else about the ICU conditions beyond the copper; doctors and nurses still washed their hands, and cleaning went on as usual. The researchers published their findings in 2013 in the journal Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (opens in new tab). Salgado and her team have also tested copper lining on stethoscopes, according to a 2017 article published in the American Journal of Infection Control (opens in new tab), where the researchers found that there were significantly fewer bacteria on copper-coated stethoscopes. In fact,66% of the stethoscopes were entirely free of bacteria. Further research is continuing to test the idea of copper plating in other medical wards, particularly in areas where patients are more mobile than in the ICU. There also needs to be a cost-benefit analysis weighing the expense of copper installation against the savings gained by preventing costly infections, Saldago said.

In 2020, a double-blind randomized control trial found that dressing cesarean section wounds in copper-rich bandages can reduce the risk of an infection within the abdominal cavity by 80% compared to traditional dressings. The results were published in the European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology (opens in new tab).

Copper also plays a huge role in electronics, and because of its abundance and low price, researchers are working to integrate the metal into an increasing number of cutting-edge devices.

In fact, copper may help produce futuristic electronic paper, wearable biosensors and other "soft" electronics, said Wenlong Cheng, a professor of chemical engineering at Monash University in Australia. Cheng and his colleagues have used copper nanowires to create an "aerogel monolith," a material that is highly porous, very light and strong enough to stand up on its own, similar to a dry kitchen sponge. In the past, these aerogel monoliths have been made from gold or silver, but copper is a more economical option.

By mixing copper nanowires with small amounts of polyvinyl alcohol, the researchers created aerogel monoliths that could turn into a sort of sliceable, shapeable rubber that conducts electricity. The researchers reported their findings in 2014 in the journal ACS Nano (opens in new tab). The ultimate result could be a soft-bodied robot, or a medical sensor that melds perfectly to curved skin, Cheng told Live Science. He and his team are currently working to create blood pressure and body temperature sensors out of copper aerogel monoliths — another way copper could help monitor human health.

Physicists have also been experimenting with copper. In a 2014 experiment, a chunk of copper became the coldest cubic meter (35.3 cubic feet) on Earth when researchers chilled it to 6 millikelvins, or six-thousandths of a degree above absolute zero (0 kelvin). This is the closest a substance of this mass and volume has ever come to absolute zero.

Researchers at the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics put the 880-lb. (400 kilograms) copper cube inside a container called a cryostat that is specially designed to keep items extremely cold. This is the first cryostat, or device for keeping things at low temperatures, that is capable of keeping substances so close to absolute zero. The icy copper experiment was part of a research project to investigate subatomic particles called neutrinos and why there is so much more matter than antimatter in the universe.

Copper is also of interest to agricultural scientists. Researchers at Cornell University (opens in new tab) have been studying the effects of copper deficiencies in crops, especially wheat. Wheat is one of the most important food staples in the world, and copper deficiencies can lead to both a lower crop yield and lower crop fertility.

The researchers have been studying how plants absorb and process the copper. They have found two proteins within the wheat, AtCITF1 and AtSPL7, that are vital to the uptake and delivery of the copper to the wheat's reproductive organs, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (opens in new tab).

Early tests have shown that when copper and other nutrients are enriched in the soil and then absorbed by the wheat, crop yields increase by as much as seven times. While the knowledge of copper and other minerals are known to be beneficial for the health and fertility of crops, the how and why of the fact is not well understood. The knowledge of why copper is beneficial and how it functions within a plant's growth and reproduction can further be used on crops such as rice, barley and oats, and can introduce these crops with a mineral-rich fertilizer, which includes copper, to soil that was once unsuitable for farming.

This article was updated on March 9, 2022, by Live Science contributor Stephanie Pappas. Additional reporting by Live Science contributor Rachel Ross.

Further reading

- The American Cancer Society (opens in new tab) examines the research about copper and claims that it may have a role in preventing or treating cancer.

- The Environmental Protection Agency (opens in new tab) provides information about exposure to high levels of copper and the effects of copper corrosion in household pipes.

- The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator facility (Jefferson Lab (opens in new tab)) explores the history and uses of copper.

Bibliography

"Copper: Element information, properties, and uses. (opens in new tab)" Royal Society of Chemistry. Accessed March 9, 2022.

"Health Benefits and Risks of Copper. (opens in new tab)" MedicalNewsToday. Updated October 2017.

"Copper (opens in new tab)." National Library of Medicine. Accessed March 9, 2022.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.