Immune System: Diseases, Disorders & Function

The role of the immune system — a collection of structures and processes within the body — is to protect against disease or other potentially damaging foreign bodies. When functioning properly, the immune system identifies a variety of threats, including viruses, bacteria and parasites, and distinguishes them from the body's own healthy tissue, according to Merck Manuals.

Innate vs. adaptive immunity

The immune system can be broadly sorted into categories: innate immunity and adaptive immunity.

Innate immunity is the immune system you're born with, and mainly consists of barriers on and in the body that keep foreign threats out, according to the National Library of Medicine (NLM). Components of innate immunity include skin, stomach acid, enzymes found in tears and skin oils, mucus and the cough reflex. There are also chemical components of innate immunity, including substances called interferon and interleukin-1.

Innate immunity is non-specific, meaning it doesn't protect against any specific threats.

Adaptive, or acquired, immunity targets specific threats to the body, according to the NLM. Adaptive immunity is more complex than innate immunity, according to The Biology Project at The University of Arizona. In adaptive immunity, the threat must be processed and recognized by the body, and then the immune system creates antibodies specifically designed to the threat. After the threat is neutralized, the adaptive immune system "remembers" it, which makes future responses to the same germ more efficient.

Major components

Lymph nodes: Small, bean-shaped structures that produce and store cells that fight infection and disease and are part of the lymphatic system — which consists of bone marrow, spleen, thymus and lymph nodes, according to "A Practical Guide To Clinical Medicine" from the University of California San Diego (UCSD). Lymph nodes also contain lymph, the clear fluid that carries those cells to different parts of the body. When the body is fighting infection, lymph nodes can become enlarged and feel sore.

Spleen: The largest lymphatic organ in the body, which is on your left side, under your ribs and above your stomach, contains white blood cells that fight infection or disease. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the spleen also helps control the amount of blood in the body and disposes of old or damaged blood cells.

Bone marrow: The yellow tissue in the center of the bones produces white blood cells. This spongy tissue inside some bones, such as the hip and thigh bones, contains immature cells, called stem cells, according to the NIH. Stem cells, especially embryonic stem cells, which are derived from eggs fertilized in vitro (outside of the body), are prized for their flexibility in being able to morph into any human cell.

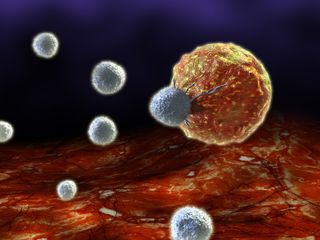

Lymphocytes: These small white blood cells play a large role in defending the body against disease, according to the Mayo Clinic. The two types of lymphocytes are B-cells, which make antibodies that attack bacteria and toxins, and T-cells, which help destroy infected or cancerous cells. Killer T-cells are a subgroup of T-cells that kill cells that are infected with viruses and other pathogens or are otherwise damaged. Helper T-cells help determine which immune responses the body makes to a particular pathogen.

Thymus: This small organ is where T-cells mature. This often-overlooked part of the immune system, which is situated beneath the breastbone (and is shaped like a thyme leaf, hence the name), can trigger or maintain the production of antibodies that can result in muscle weakness, the Mayo Clinic said. Interestingly, the thymus is somewhat large in infants, grows until puberty, then starts to slowly shrink and become replaced by fat with age, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Leukocytes: These disease-fighting white blood cells identify and eliminate pathogens and are the second arm of the innate immune system. A high white blood cell count is referred to as leukocytosis, according to the Mayo Clinic. The innate leukocytes include phagocytes (macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells), mast cells, eosinophils and basophils.

Diagram of the immune system

Diseases of the immune system

If immune system-related diseases are defined very broadly, then allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis, asthma and eczema are very common. However, these actually represent a hyper-response to external allergens, according to Dr. Matthew Lau, chief, department of allergy and immunology at Kaiser Permanente Hawaii. Asthma and allergies also involve the immune system. A normally harmless material, such as grass pollen, food particles, mold or pet dander, is mistaken for a severe threat and attacked.

Other dysregulation of the immune system includes autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

"Finally, some less common disease related to deficient immune system conditions are antibody deficiencies and cell mediated conditions that may show up congenitally," Lau told Live Science.

Disorders of the immune system can result in autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases and cancer, according to the NIH.

Immunodeficiency occurs when the immune system is not as strong as normal, resulting in recurring and life-threatening infections, according to the University of Rochester Medical Center. In humans, immunodeficiency can either be the result of a genetic disease such as severe combined immunodeficiency, acquired conditions such as HIV/AIDS, or through the use of immunosuppressive medication.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, autoimmunity results from a hyperactive immune system attacking normal tissues as if they were foreign bodies, according to the University of Rochester Medical Center. Common autoimmune diseases include Hashimoto's thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus type 1 and systemic lupus erythematosus. Another disease considered to be an autoimmune disorder is myasthenia gravis (pronounced my-us-THEE-nee-uh GRAY-vis).

Diagnosis and treatment of immune system diseases

Even though symptoms of immune diseases vary, fever and fatigue are common signs that the immune system is not functioning properly, the Mayo Clinic noted.

Most of the time, immune deficiencies are diagnosed with blood tests that either measure the level of immune elements or their functional activity, Lau said.

Allergic conditions may be evaluated using either blood tests or allergy skin testing to identify what allergens trigger symptoms.

In overactive or autoimmune conditions, medications that reduce the immune response, such as corticosteroids or other immune suppressive agents, can be very helpful.

"In some immune deficiency conditions, the treatment may be replacement of missing or deficiency elements," Lau said. "This may be infusions of antibodies to fight infections."

Treatment may also include monoclonal antibodies, Lau said. A monoclonal antibody is a type of protein made in a lab that can bind to substances in the body. They can be used to regulate parts of the immune response that are causing inflammation, Lau said. According to the National Cancer Institute, monoclonal antibodies are being used to treat cancer. They can carry drugs, toxins or radioactive substances directly to cancer cells.

Milestones in the history of immunology

1718: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, observed the positive effects of variolation — the deliberate infection with the smallpox disease — on the native population and had the technique performed on her own children.

1796: Edward Jenner was the first to demonstrate the smallpox vaccine.

1840: Jakob Henle put forth the first modern proposal of the germ theory of disease.

1857-1870: The role of microbes in fermentation was confirmed by Louis Pasteur.

1880-1881: The theory that bacterial virulence could be used as vaccines was developed. Pasteur put this theory into practice by experimenting with chicken cholera and anthrax vaccines. On May 5, 1881, Pasteur vaccinated 24 sheep, one goat, and six cows with five drops of live attenuated anthrax bacillus.

1885: Joseph Meister, 9 years old, was injected with the attenuated rabies vaccine by Pasteur after being bitten by a rabid dog. He is the first known human to survive rabies.

1886: American microbiologist Theobold Smith demonstrated that heat-killed cultures of chicken cholera bacillus were effective in protecting against cholera.

1903: Maurice Arthus described the localizing allergic reaction that is now known as the Arthus response.

1949: John Enders, Thomas Weller and Frederick Robbins experimented with the growth of polio virus in tissue culture, neutralization with immune sera, and demonstration of attenuation of neurovirulence with repetitive passage.

1951: Vaccine against yellow fever was developed.

1983: HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) was discovered by French virologist Luc Montagnier.

1986: Hepatitis B vaccine was produced by genetic engineering.

2005: Ian Frazer developed the human papillomavirus vaccine.

Additional resources:

- UCSD: A Practical Guide to Clinical Medicine

- Harvard Medical School: How to Boost Your Immune System

- NIH: Overview of the Immune System

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice. This article was updated Oct. 17, 2018 by Live Science Health Editor, Sarah Miller.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Kim Ann Zimmermann is a contributor to Live Science and sister site Space.com, writing mainly evergreen reference articles that provide background on myriad scientific topics, from astronauts to climate, and from culture to medicine. Her work can also be found in Business News Daily and KM World. She holds a bachelor’s degree in communications from Glassboro State College (now known as Rowan University) in New Jersey.